Las Aves aboard Blue Manta

Las Aves aboard Blue Manta

Las Aves aboard Blue Manta

Las Aves aboard Blue Manta

Las Aves aboard Blue Manta

Las Aves aboard Blue Manta

Though officially not part of the ABC islands, any book about the history of the ABCs wouldn’t be complete without a few words about the Archipelago of Las Aves. This spectacular Venezuelan coral atoll is a real hot spot for shipwrecks and a major component in the history of Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao.

To get to Las Aves you’ll need a handful of courage and a bowl of very thick porridge in your gut. Only accessible by boat, Las Aves is a twenty-hour sail from the southern tip of Bonaire. Once past the island of Bonaire, it’s high, wide-open sea all the way—and worse, it’s sailing completely against the waves. The southwesterly wind of Alezes blows directly opposite your course, forcing you to tack as many as twenty times during the trip.

On the horizon, Las Aves is almost invisible. In the south, you can vaguely make out an island, which closes Las Aves’ hidden crescent-shaped reef at its southernmost tip. As you get a bit closer, several other islands come into view. On the western side, Las Aves’ few barren sandbar islands provide shelter from the wind and waves—and a comfortable place to anchor a boat.

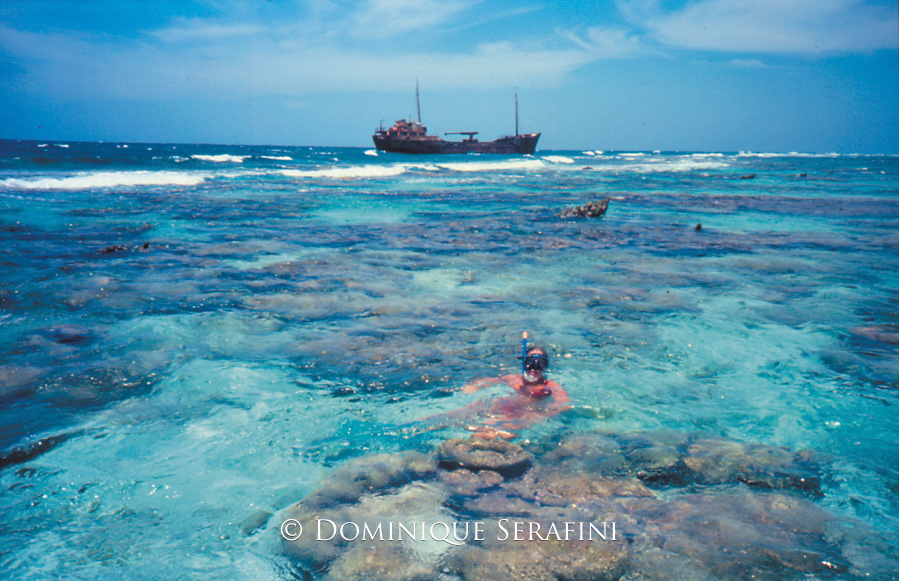

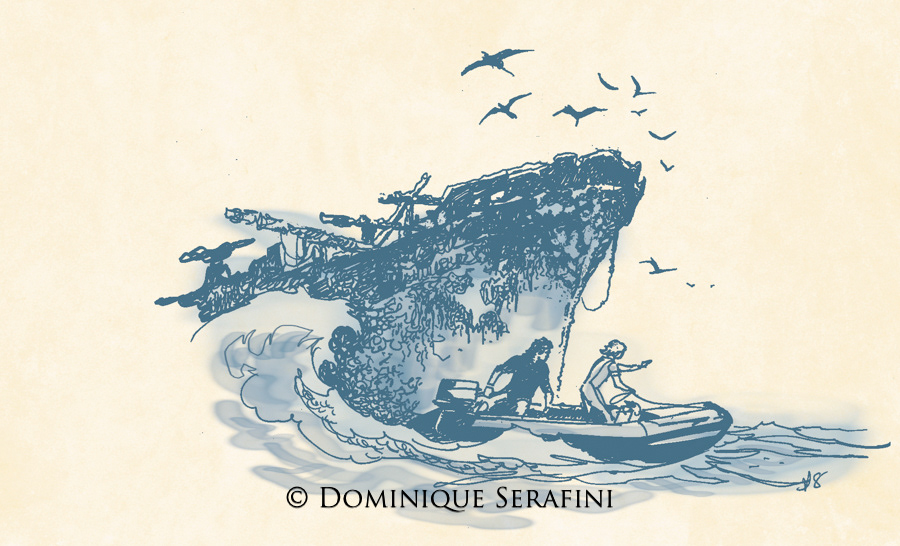

But shipwreck hunters don’t stop there. In search of sunken vessels, you need to cross Las Aves’ lagoon, avoiding large coral patches the length of the trip. Colors change from turquoise to green-blue to deep-blue as you work your way through this liquid maze. Clear on the other side of the lagoon is a true barrier reef, with a solid line of white waves crashing down on the coral, which peeps just above the surface. On the breakpoint are the silhouettes of two ships: Like sentinels, a wrecked tanker to the north and a sunken freighter to the south stand above the waterline on the barrier reef. They are clear reminders of the potential dangers this hidden reef poses to ships arriving from the east.

On this reef, encrusted in coral, lie dozens of cannons, anchors, chains and metal pieces from seventeenth-century vessels. These are the remaining vestiges of twelve French galleons that sunk in Las Aves in 1678.

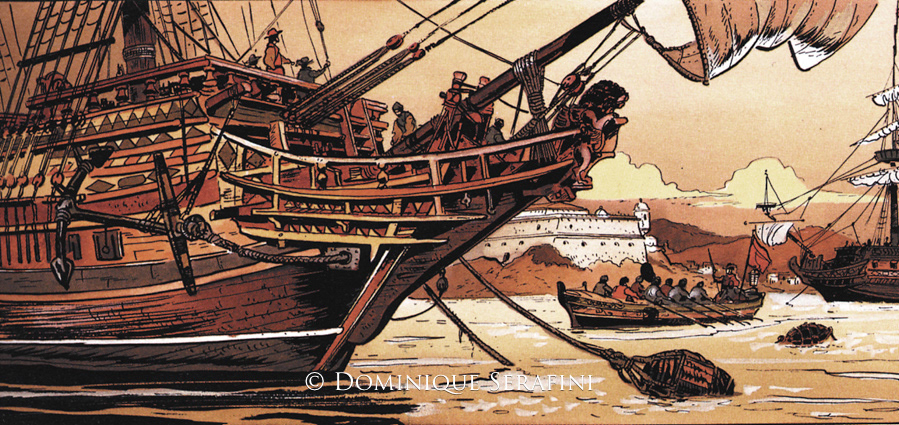

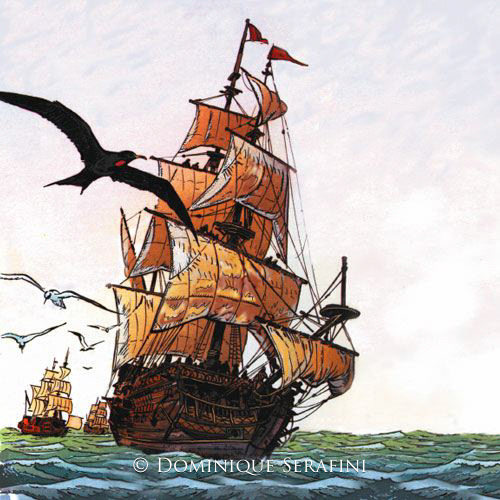

In the late 1600s a campaign of battles was fought throughout the Caribbean for the colonial occupation of the islands. The French won many victories against the English. Under the direction of Admiral d’Estrées, the French easily captured the colonies of St Lucia, St Vincent, Grenada and Trinidad. In 1678, by order of the King of France, d’Estrées was sent on a mission to conquer the Dutch-occupied islands of Bonaire and Curaçao.

To the French, the expedition seemed a simple one. D’Estrées, intoxicated by his prior victories in the north, was sure the Dutch would crumble with just a few cannon shots. With a well-planned attack and a fleet of eighteen vessels and thousands of men, the odds would be in his favor. For added firepower, he invited pirate and mercenary ships to join the expedition, promising them part of the loot. Looking for a conclusive victory, d’Estrées didn’t realize that in amongst the mercenaries were a few Dutch spies.

And so, with his elaborate plan, d’Estrées’ fleet set sail from Trinidad. The wind pushed the armada along the coast of Venezuela and past the Archipelago of Los Roques towards Bonaire.

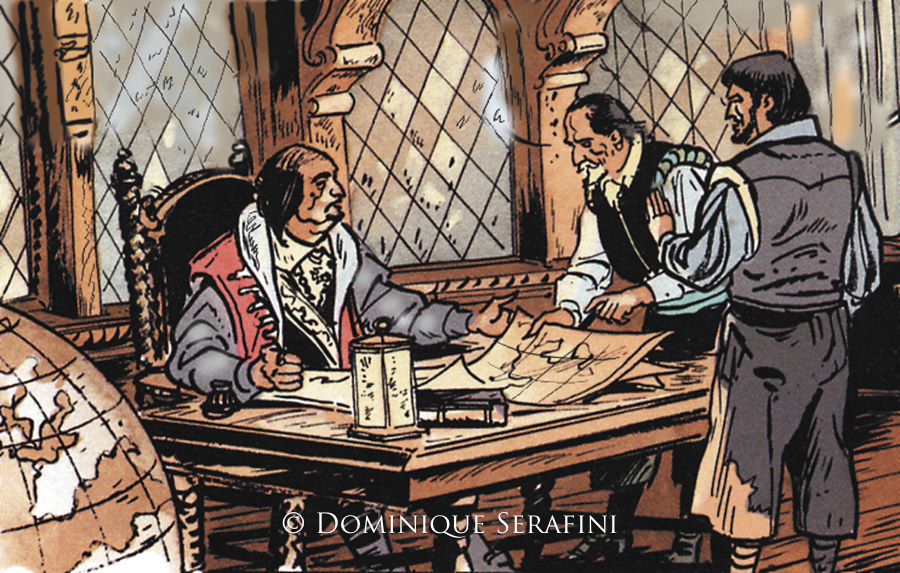

Informed of the oncoming danger, Dutch officials knew they were facing a potential disaster, as their army in Curaçao was too weak to resist such a large attack by the French. But Holland was definitely not prepared to surrender these prize islands, which furnished salt to the fisheries.

Confident in their superior knowledge of the southern Caribbean as well as their excellent seamanship, the Dutch laid their trap. D’Estrées, lacking in sailing experience and far too confident, was to be an easy mark.

A small fleet of Dutch boats set sail from Curaçao destined for Las Aves. Once assembled on the Venezuelan archipelago, the Dutch maneuvered their ships into the heart of Las Aves’ lagoon and waited for the arrival of the French, en route to Bonaire. As night fell, lanterns were lit. Simulating the lights of a town, the Dutch sailors hoped to convince the French that they had reached Bonaire. In so doing, they could attract the French galleons onto the reef.

As the French fleet approached Las Aves, d’Estrées’ vigil spotted the lights. Against the advice of his captains and navigators, the Admiral headed his ship—le Terrible—straight for the trap and directly towards the coral reef. By the time the breakers were spotted, it was too late. Le Terrible, too heavy to veer into the wind, couldn’t avoid the reef.

To warn the rest of the armada, le Terrible fired its cannon. But the signal was misinterpreted as a call for help, and one by one, the rest of the boats in the fleet headed towards the reef. Pushed forward by the waves, the vessels touched bottom and implanted themselves in the reef, without a chance of breaking free.

A few vessels had time to veer away. One ship was able to rescue d’Estrées and many of his senior officers, avoiding their capture by the Dutch. The vessel beat a hasty retreat from Las Aves, abandoning a thousand or more soldiers, condemning them to a slow death on the reef or capture by the Dutch.

Back in France, accused of abandoning his men, d’Estrées was court-martialed. But given his tight relations with the French nobility, he wasn’t condemned. Soon after, a peace treaty was signed between the Dutch, French, English and Spanish regarding the islands of the Caribbean. And the Dutch kept their colonies of Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao.

Perhaps, if the Admiral had been more cunning, we all might have ended up in Bonaire under the French flag, eating steak-frit while drinking red wine and playing the accordion.

This page in the history of the French navy is not a glorious one and has all but been forgotten. Very little documentation of the expedition still exists. The extracts of the court case were preserved and are at the Musée de la Marine in Paris. That’s where we found an officer’s testimony together with an extremely precise map of where the twelve vessels sunk on the reef.

Over the years, there have been many wreck-hunting expeditions to Las Aves. Explorers have come and gone in vain, searching for galleon treasures. It isn’t the extreme underwater depths that posses the difficulties. On the contrary, it is the fact that there is hardly any water. The relics are close to the surface where the coral grows most prolifically and where the waves break hard, making underwater exploration and recovery very difficult. In fact many expeditions have ended with broken teeth.

Nowhere else in the Caribbean can you find so many seventeenth-century galleon relics. On most other islands, wreck hunters have tampered with or removed these rare gems.

In Las Aves, anchors, cannons and other boat parts are spread out over an immense surface area of about seven miles. Imagine how many relics exist, given that on le Terrible alone there were seventy cannons of differing size. In a forest of staghorn coral and covered by fire coral, it really takes a well-tuned eye to be able to distinguish the artifacts from dead pieces of coral.

The largest cannon that we found was completely by fluke—when Dominique stood up on the rubble bed below. While staring down at his fins, Catherine's eyes were drawn to the nine-foot cannon that he was standing on.

In the course of our search, we found many cannons but all of them iron. The large bronze cannons, which were on board the French fleet, were more than likely removed by the Dutch after the ambush—with the "help" of the captured French soldiers.

Of the thirteen vessels that hit the reef, one managed to disengage. But while trying to make an evasive turn around the reef, it sank in deeper water. To reach this wreck you must cross to the outside of the reef, passing a labyrinth of coral while fighting the breakers. This isn’t a small adventure and can often be acrobatic.

Your other choice is to wait until the wind dies down and then leisurely swim across the reef. That’s our preferred method. With our catamaran anchored in the lagoon, we wait, completely losing track of time.

For us, like the Admiral, Las Aves is a trap. We are trapped by the marvels of the place and return often. Las Aves has purity, tranquility and beauty, not to mention the bands of large fish and the gorgeous coral formations. It’s a real treasure that has no price. During one of our visits, a curious seven-foot barracuda started living under the catamaran, waiting for the scraps off our plates. "Monsieur Jules" quickly becomes a part of daily life every time we return.

You see, Las Aves is one of the last remaining virgin sanctuaries in the Caribbean, not touched by tourism. Searching for anchors and cannons becomes just a pretense for being there.

Shipwrecks of Las Aves

Shipwrecks of Las Aves

Shipwrecks of Las Aves

Shipwrecks of Las Aves

Shipwrecks of Las Aves

Shipwrecks of Las Aves

Shipwrecks of Las Aves