The Windjammer, Bonaire by Dominique Serafini

As told by Dominique Serafini:

In the spring of 1997, I set sail from the Grenadine Islands aboard my catamaran, Blue Manta, in search of spectacular diving and exciting shipwrecks. I sailed westward along the coast of Venezuela, passing the islands of Tortuga, Blanquilla, Margarita and Las Aves. My heading was Bonaire—as I had heard vague references of a magical and virgin wreck sitting just off the island’s coast.

Hidden in the back pages of a Skin Diver magazine, I had read an article about a fabulous Bonairian wreck called the Windjammer. And in a lesser-known work by MichaelCrichton—the author of Jurassic Park—there was an entire chapter about Crichton’s life-threatening dive experience on the Windjammer. I knew that somewhere off the shores of Bonaire, in about 200 feet of water, lay this mysterious clipper, a vessel of magical mystique which has been enticing divers and novelists down to its depths since the late 1960s.

My search for the Windjammer’s whereabouts began simply, with inquiries around the island at local dive shops. But my quest turned out to be anything but simple. Much to my surprise, no one seemed to know where I might find this illustrious ship. One elusive answer followed the next. I suspected that I was being kept out of the loop and felt quite estranged, much like a visitor to Transylvania in search of Count Dracula. At the local bookstore, I scanned the pages of several regional dive guides but nowhere was there a reference to the Windjammer. There seemed to be an island-wide blackout on the subject, and my search for the Windjammer was temporarily dead in its tracks.

Several months later, I would meet a renegade dive operator who was willing to share the whereabouts of the Windjammer and to guide me to that secret spot.

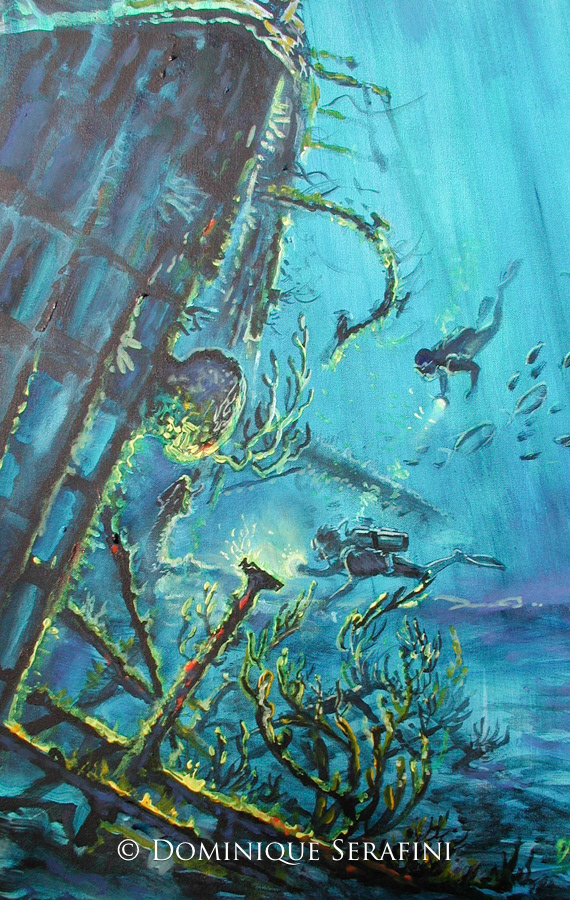

And on a memorable morning, from a secluded part of Bonaire’s shoreline, my newfound informant and I made our first dive on the wreck. On the drop-off, at quite a distance from the shore, lay a metallic mast, covered with sponges of many colors. In 30 feet of water, its base pointed towards the deep, indicating the position of the wreck. No doubt, this mast had served as a directional signpost and a seductive force for many divers over the years.

The Windjammer, Bonaire by Dominique Serafini

At the base of this mast, we left two extra tanks, which we had brought for our anticipated decompression stops. Into the deep blue we descended, pulled beyond the reef by a strong current. As we hit 120 feet, from out of nowhere, the ominous silhouette of the large vessel suddenly appeared.

It was breathtaking. Lying on its starboard side in 200 feet of water was the Windjammer. Like the spiny back of a giant reptile, the sharp profile of the keel traced a long line in the white sand. Swimming over the side of the ship, we took a quick glimpse at its impressive hull, waiting for us below. Fifty feet further down on the sand lay the ship’s two remaining masts, attached and entangled in their cabling. The bowsprit pointed forward across the sand, with all its rigging intact and hanging. And the rib-like skeleton of the hull, covered with sponges and black coral, was like the door to a haunted house.

I was entranced. Schools of jacks swam the length of the wreck. The beam of my flashlight shined brightly on a big grouper. The sound of our regulators and the allure of our lights had intrigued this peaceful monster, which quickly retreated into the darkness. Two huge barracudas followed closely behind.

But suddenly, the spell was broken—our dive computers, depth gages and chronometers signaled us to our senses. The magical charm of the wreck vanished. It was time to start our ascent to the mast to find our reserve tanks for our lengthy decompression stops.

As I fought against the strong current, pushing me out to sea, I understood the great dangers of this wreck, and why dive operators guarded the whereabouts of the Windjammer with such discretion.

The Windjammer, Bonaire by Dominique Serafini

For the untrained diver, the Windjammer is the perfect trap. On some days, with visibility of more than 100 feet, the wreck doesn’t seem so deep. And the temptation to go far inside the hull is almost too great to resist. Mix in a little nitrogen narcosis and you don’t see the precious time ticking away, nor notice your air being consumed at an unusually high rate. Strong currents pull you away from the coast, far from your decompression tank sitting somewhere back on the reef. This dream wreck could easily become a nightmare.

In my attempts to draw the Windjammer, I have made many dives on this wreck since that first time. Between the short bottom times and the large size of the vessel—239 feet long—it took hundreds of dives to complete my paintings. Most days, I dove the Windjammer alone with a drawing board, sketching the many angles of the ship.

As I penetrated deeper into the hull, I became more and more engrossed in the legends surrounding this mystery ship. Although it had been known for many years as a ghost wreck, I had yet to find the infamous ghost.

Then one day, while inside the hull and completely absorbed in sketching some small detail of the ship, I felt a presence. I heard bubbles that were not mine. Out of the shadow came a white-haired man with cunning blue eyes. A wave of his hand and he was gone into the darkness, leaving nothing behind but a trace of bubbles.

It was an hour later on the shore when I finally met up with this strange visitor. He promptly marched out of the water, sat down next to me, took off his mask and, with a strong Scottish accent, said, "What the hell are you doing on my wreck?"

The Windjammer, Bonaire by Dominique Serafini

This is how I met Maurice D. Coutts, a 68-year-old Scotsman from Princeton University in the United States. Maurice, a seasoned diver, had been instrumental in the development of the decompression tables for the British navy. A man of great distinction, he kept company with legendary divers including Jacques Cousteau.

It was in 1968 when Maurice and fellow divers Harry Engelhardt, Percy Sweetnam and Captain Don Stewart first discovered the Windjammer. Each year since, Maurice had made his pilgrimage to Bonaire to spend a month doing nothing else but diving the wreck. Thirty years later when I met Maurice, he knew every square inch of the vessel.

That evening, Maurice asked me if I would accompany him on further dives on the wreck, promising he could show me details of the ship that I had never seen. Naturally, I was elated.

But first, he insisted that I must change my dive equipment to accommodate the additional safety concerns of a 200-foot, 15-minute dive. From that day forward, I dove with two 12-liter tanks on my back and a six-liter tank of oxygen strapped to my bc, which I used to finish up my last decompression stop at 10 feet.

He wrote out and handed me the deco stops he had been using for years: 40 feet for 1 minute, 30 feet for 4 minutes, 20 feet for 10 minutes and 10 feet for 23 minutes.

The Windjammer, Bonaire by Dominique Serafini

On subsequent dives, he showed me some of the more intimate parts of the Windjammer: the anchor still on the deck, the boiler engines, the last untouched bottle of Italian wine. Typically, we would dive around noon, when the sun’s rays penetrated the lattice of the hull, transforming the clipper into an underwater cathedral. The incandescent blue and the shimmering light reminded Maurice of the cathedral in Chartres, France, where he had been as a child.

After the dives, back on the shore, he would crack Scottish jokes and speak of his ancestors fighting at Waterloo against the bloody French. One day, Maurice showed up for our daily dive in a Scottish kilt and cap with a bottle of single-malt in hand. That day we sat on the shore, and he recounted the history of the clipper, which he had pieced together with the help of the insurance records kept by Lloyd’s.

For years, Maurice’s friend, Captain Don, tried to convince him to stop diving the Windjammer. Don knew that Maurice had suffered a heart attack years back and the risks for the old man were very high. But Don’s words fell on deaf ears. Maurice well knew the limits of deep diving, and understood his much-increased health risks. But he chose to continue diving the Windjammer, balancing that risk against his endless passion for the vessel.

The Windjammer, Bonaire by Cathy Salisbury

On December 2, 1997, after a wonderful dive with Maurice on the wreck, he didn’t surface. I finished my 10-foot decompression stop and left the water, waiting for my friend on shore. I eventually found him, one hour later, in 30 feet of water, peacefully lying on a bed of white sand between two coral heads. His mask was on, his eyes open and he had a smile on his face. For a split second, I thought it was another one of his Scottish jokes. But this time it wasn’t. The old Scotsman’s heart had stopped beating and Maurice lay dead. As there was no sign of panic like a yanked weight belt or a pumped-up bc, I often imagine his death as being quite a peaceful one.

My first impulse was to help Maurice return to his wreck by carrying out and releasing his body into the blue. Though I’m quite sure he would have wanted it that way, I knew it would not be appreciated by his family—or by the police officers who I would later meet on the shore. So I released Maurice’s weight belt, inflated his bc, and watched his body float up to the surface. With the help of two fishermen, I brought Maurice’s body back to the shore where his dive computer was confiscated and the investigation began. Police officers hoped to unravel the mystery of Maurice’s death. Depths and times they discovered but the incalculable passion of an old diver for his wreck, they will never know.

If you ever want to dive the Windjammer, it is up to you to play detective. The surprise is well worth the effort. But be prepared: The depth of the dive combined with frequently strong currents makes it a dive for experienced and well-trained divers. And if you do discover the secluded spot on which the Windjammer lies, don’t be alarmed if you meet a ghost. It’s just Maurice, making a visit to his Scottish clipper.

The Windjammer, Bonaire by Dominique Serafini

The Windjammer, Bonaire by Dominique Serafini

The Windjammer, Bonaire by Dominique Serafini

The Windjammer, Bonaire by Dominique Serafini

The Windjammer was one of a series of three-mast iron ships, each designed for speed on the long haul shipping goods between England and India for the MacIntyre Company. Built in Glasgow, Scotland in 1874 by Barclay, Curl and Company, it measured 239 feet long, weighed 378 tons and had a 37-foot beam. Nicknamed the Windjammer, the ship officially sailed under the name the Mairi Bhan, Gaelic for “the Bonnie Mary.”

The Windjammer made its maiden voyage from Glasgow to New Zealand in a record seventy-five days. Like the Cutty Sark, the Windjammer was one of the fastest boats ever built. The ship continued its illustrious career, sailing all over the world until 1890.

As the power engine began to revolutionize the shipping industry, many companies such as MacIntyre, vested in sailing ships, had severe financial difficulties. Consequently, the clipper was sold to Bengris & Morzola, an Italian company based in Genoa. Without a permanent route to work, the Windjammer moved from port to port, picking up more-or-less legal cargo as it went.

Loaded with olive oil, Italian wines, marble and clothing, the ship set sail on its last trip—from Genoa to Trinidad and then back to Marseilles. While in Trinidad, the ship picked up some unforeseen cargo, namely asphalt, and headed towards the coast of Venezuela.

In December 1905, the ship docked in the port of Kralendijk, Bonaire. The reputation of Captain L. Razeto and his merry band of bandits preceded him and the Bonaire harbormaster ordered the ship out of the harbor.

The Windjammer, Bonaire by Dominique Serafini

The Windjammer, Bonaire by Dominique Serafini

On December 7, the ship left the port of Kralendijk, hitting the reef at the deserted northern end of the island. How the clipper went aground, no one knows. Was there a fire on board? Severe winds? There are many dramatic versions of the story. Maurice, who studied the Lloyd’s archives, believed the end of the Mairi Bhan to be less dramatic. After forty years of sailing, the clipper was taking on water through the hull rivets. Maurice believed that the weary sea captain chose to run the boat ashore rather than sink at sea.

With the Mairi Bhan lodged on the reef, the captain and crew abandoned the ship, carrying all that they could potentially sell.

For Bonairians, the crash of this big clipper was like an early Christmas present. With axes, they salvaged the wood from the bridge, the ropes, the sails, the copper, the nails and the rigging—they skinned the carcass of the old clipper. After several weeks of carnage the main mast fell, killing two people.

Finally in 1912, a hurricane dislodged the Mairi Bhan from the reef and the ship rolled, capsized and sank to the bottom of the sea.

Among fishermen of Rincon, the tale of the Mairi Bhan is still very much alive. Legend says that the ship didn’t sink—it simply vanished. One day she will return to the shores of Bonaire, seeking revenge against all those who salvaged parts of her rigging.

Predominantly used as chartered sailing vessels, other clippers of the Windjammer series have sailed the waters of the Caribbean. But in 1999, off the coast of Honduras, the last of the Windjammers mysteriously vanished. Apparently the captain heard of an impending hurricane, leaving his one hundred and fifty passengers at the nearest port to head out to sea with his crew to fight the storm. All that was ever found was a buoy on which the name of the ship—Phantom—was written.

The Windjammer, Bonaire by Dominique Serafini