Aruba's Antilla shipwreck by Cathy Salisbury

Sixty years ago, Aruba wasn’t a tourist paradise. There were no hotels or glitzy casinos. No duty-free shops. Instead, Aruba’s economy was primarily based around the large oil refinery of San Nicolas at the south end of the island. A short distance from the Venezuelan oil fields of Lake Maracaibo, the Lago and Shell refineries were strategically placed in Aruba.

During the Second World War, Aruba became the fulcrum of oil supply for the Western Hemisphere. From Aruba poured aviation gasoline and motor fuels critical to the Royal Air Force fighters and bombers; for the British Eighth Army guarding the Suez Canal as well as for the growing American military forces. Aruba was charged with keeping American tanks, planes and ships full of fuel and on the move. Producing one out of every sixteen gallons of motor fuel consumed during WWII, Aruba was an important spot on the world map.

Aruba’s petroleum complex occupied the attention of the German Third Reich strategists. Even before the first bloodshed in Europe, the secret service of the Aberwher had sent numerous spies to Aruba to plot sabotage missions against the petroleum refineries.

In 1939, the Germans secretly deployed numerous U-boats across the Atlantic to the coast of South America. Five of these submarines were to make the ABC islands their base. Called the Neuland Gruppe, their mission was to attack Aruba and Curaçao’s refineries and to torpedo tankers carrying crude oil to the refineries from the Venezuelan oil fields in Lake Maracaibo. Like a pack of gray wolves, the Neuland Gruppe’s U-boats crossed the Atlantic. Arriving in the Netherland Antilles, they prowled the waters of Aruba and Curaçao, looking for quiet bays in which to hide and await orders to attack.

Serving as supply boats for these submarines were two big German freighters, circulating in the waters of Aruba. The bigger of the two, the Antilla, was a 400-foot vessel, built in 1938 in Hamburg. Under the guise of a peaceful, commercial freighter working in the neutral waters of the Dutch islands, the Antilla secretly housed all supplies needed for the submarines and their crew, including a deadly arsenal—torpedoes, mines and other munitions.

In the bars of San Nicolas, the crew of the Antilla spent their evenings fraternizing with Dutch and American soldiers, sailors and petroleum company employees, seeking out delicate details about the oil operations of the island. Charlie’s Bar was the hotbed for these spies, where suspicious people traded in false truths while casually sipping their whiskies. But this camaraderie ended the day Adolf Hitler took an aggressive position towards Holland. Without even a declaration of war, Hitler’s Wehrmacht attacked Holland, much to the surprise of the Dutch motherland and her colonies.

Suddenly, Germany was officially at war with Holland and the captain of the Antilla feared the repercussions. With the American Navy patrolling the open waters of the Caribbean, the captain hesitated to leave Aruba’s coast. Anchored at the northern point of Aruba in a remote inlet called Lighthouse Bay, he felt somewhat sheltered both from the Dutch and from the Americans.

But the Dutch reacted quickly to the German enemy presence. In the middle of the night, rowing silently with their lights dimmed, a team from a small Dutch patrol ship boarded the Antilla. The Dutch demanded the immediate surrender of the ship—leaving the captain no choice but to comply. In return, the captain asked fora few minutes to gather his personal possessions, which the Dutch courteously extended to him.

Taking advantage of this borrowed time, the captain went about sabotaging his ship—overheating the boilers, opening valves, closing drains and, finally, blasting a hole in the side of his freighter. The ship was cut in two and sunk in less than 60 feet of water; the mast and chimney still emerging from the water. Needless to say, the Dutch patrolmen were furious at having being fooled. Having thought they could appropriate the freighter for their own use, they were dumbfounded and powerless as they watched the Antilla sink. The Antilla was unrecoverable.

Meanwhile the war raged on in Europe and thousands of naval soldiers died in the Atlantic and the North Sea. The captain and crew of the Antilla finished the war quietly—imprisoned in a beachfront POW camp in Bonaire that they shared with German civilians, political refugees and Jewish people.

A real paradox, the captain of the Antilla found the Bonairian prison camp so beautiful that after the war he refused to go back to Germany. Instead, he, together with some partners, bought the prison from the Dutch Antilles and built a hotel on the land. Today that hotel is called Divi Flamingo.

To finance the purchase of the land and the construction of the hotel, the captain looked no further than the hull of the Antilla. After the war, the captain went back to his freighter to fetch a very valuable cargo. Still housed in the freighter’s infirmary locker were thousands and thousands of vials of morphine, worth a small fortune. This true-life story inspired American author Peter Benchley to write his book The Deep.

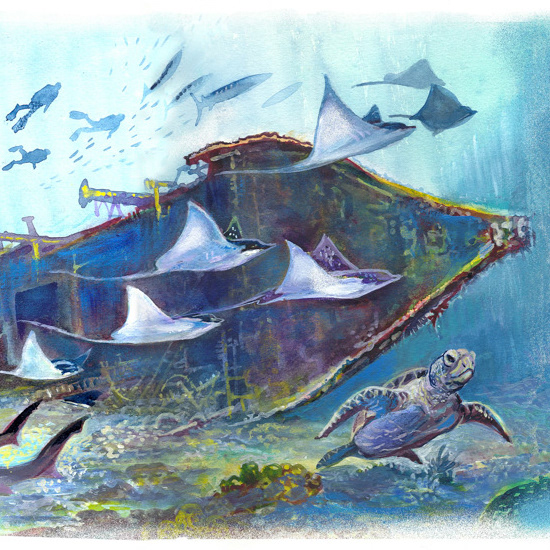

The captain of the Antilla gave the dive operators of Aruba a great gift by scuttling his vessel in shallow waters. Lying on a bed of superb white sand, not far away from the coast and protected from the swell, the Antilla is a golden wreck for today’s divers, a real war treasure. It is very easy to find, the bow sticking out of the sea. Upon the bow, cormorants, pelicans and sterns regularly perch, looking at the prolific fish population that lurks below, inhabiting the wreck.

Every morning by 10am, an armada of tourist boats comes to the wreck—pirate ships, catamarans, dive boats, glass-bottom boats and even a submarine—bringing hundreds and hundreds of divers and snorkelers daily. The fish of the wreck gather near the surface, waiting to be hand-fed. Yellow-tailed snappers, barracuda, rays and groupers put on quite a show for their supper.

To the blasé, highly experienced wreck diver, the Antilla may appear too easy and commercial. But that’s a mistake. Despite all the tourist activity, this wreck has some real choice morsels.

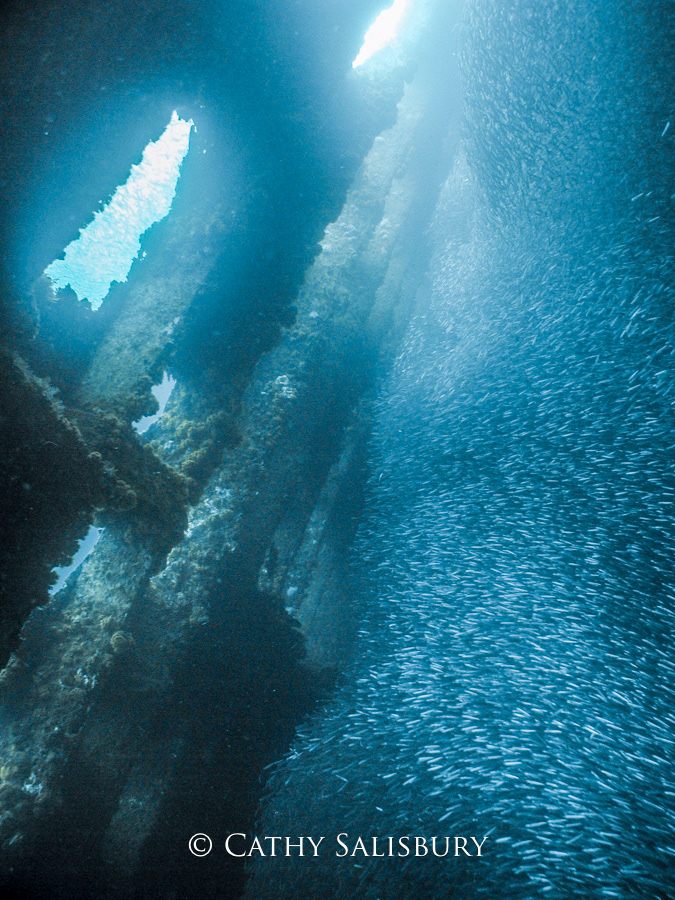

Early in the morning before 10am, between noon and 2pm, or at the end of the day, the wreck is deserted. And it looks grandiose. In the immense hull, the light plays through the portholes. Swarms of silversides fill the cargo hulls, creating elaborate circular forms as they pulsate in unison before your eyes. Between the rigging cables, the shiny silhouettes of barracudas sparkle. It’s an absolute pleasure to the eye and to the camera lens.

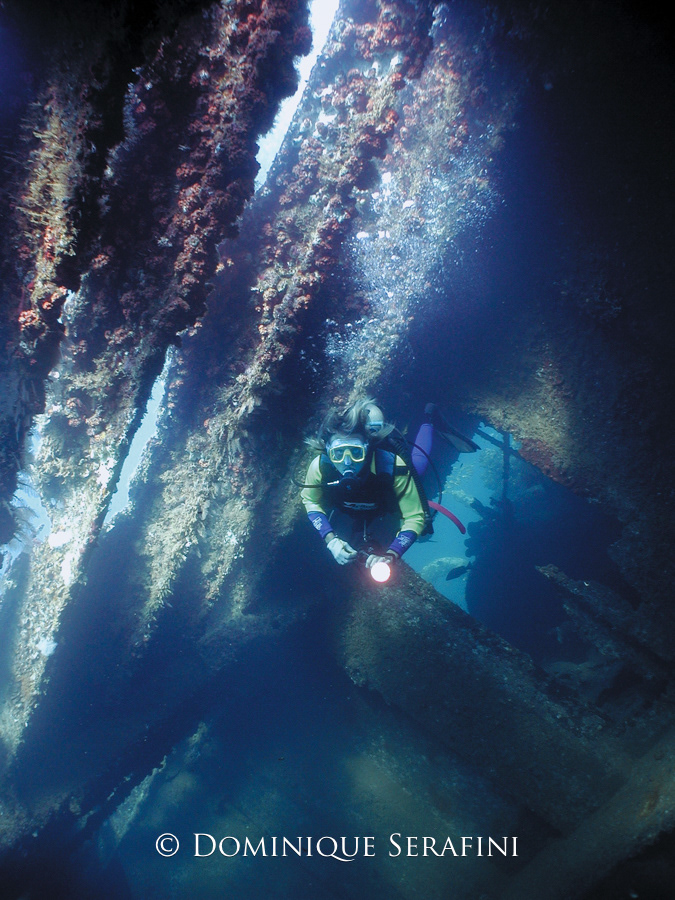

The Antilla, Aruba by Dominique Serafini

The Antilla, Aruba by Dominique Serafini

The Antilla, Aruba by Dominique Serafini

The Antilla, Aruba by Cathy Salisbury

The Antilla, Aruba by Dominique Serafini

The Antilla, Aruba by Dominique Serafini

The Antilla, Aruba by Dominique Serafini

You can easily be led astray, down the endless corridors of the wreck, where you can still find some locked doors. The spectacular light, deep inside the cargo hulls, evokes great illusions of depth while you are no deeper than 50 feet. You can linger in the labyrinth without worrying about breaking non-decompression tables.

And for treasure seekers, there are still undiscovered artifacts buried in the sand around the wreck, waiting to be exhumed—grenades, munitions, knifes and guns bearing sinister swastikas.

Though a long swim from the shore, the Antilla can be done as a shore dive. Go around noon hour and you can enjoy a quiet moment out at the wreck. But beware of the boat traffic—there is a lot of it. For safety reasons it is a good idea to make yourself visible by carrying a surface marker or other indicator.